It's not 100% finished and there are many things to polish. Especially taking into account my beginner level of Rust, but let me start by explaining a little bit about how it all works. Let's remember first the requirements from the previous blog post:

Logging in = Post with an email + password to the service. The service will verify the password, return an unauthorized response or accept with a generated JWT.

To be able to do that, there is another needed functionality, that one of registering users.

We will focus first on the registration part of the application. Let's begin!

Cargo

Cargo is a must to work with Rust. Even me a beginner of rust can tell you that. Check the oficial documentation on how to install Cargo. You definitely need that.

The project directory structure

We will create an explicit hexagonal architecture folder structure.

You can use cargo to create the project: cargo new your-name-of-project

Inside src we will create three folders: domain, application and infrastructure.

├── Cargo.lock

├── Cargo.toml

├── src

│ ├── application

│ ├── domain

│ ├── infrastructure

│ └── main.rs

we will focus only on the domain for most of the time. Why? Because we are doing DDD!

Include files in the project

First thing first, we want cargo check to see the stuff that we put inside the domain (to start with).

Disclaimer again for my ignorance of rust, but I haven't found a way I really like to include files, I am

sticking to a way that just works but I find it very cumbersome, too much manual work, having to write all the includes by hand. One of the reasons it looks very cumbersome is that I don't think many people use this explicit hexagonal architecture directory structure in Rust projects. Sorry for being a zealot for that! It would be nice that somebody can tell me a better way than the one I am going to explain here, but so far this is how we're going to do it.

On the Cargo.toml, we will tell it that we are going to use both main and lib:

#cargo.toml

[lib]

path = "src/lib.rs"

[[bin]]

path = "src/main.rs"

name = "crappy-user"

(Now that you are looking at that file, feel free to change the information under "package").

Then, create a lib.rs file where we will add all the "modules" that our app will have (namely, the 3 directories we just created before.)

We will start only with the domain first.

so lets begin, create a file next to main.rs, called lib.rs with these contents:

//src/lib.rs

pub mod domain;

On the domain directory we will create a file 'mod.rs' that will have all the includes of our "domain" module:

//src/domain/mod.rs

mod user;

pub(crate) mod user_tests;

pub use user::*;

I am going one step ahead here. I am adding already the tests, but on a different file, contradicting what the (rust book)[doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch11-03-test-organiz.. says:

The convention is to create a module named tests in each file to contain the test functions and to annotate the module with cfg(test) [for unit tests]

well, I already know that the code for the tests is going to be almost twice as long as the user aggregate, that's why I already put it in a different file.

Ok you may create the files that we said rust we are adding, so you have something like this:

src/

├── application

├── domain

│ ├── mod.rs

│ ├── user.rs

│ └── user_tests.rs

├── infrastructure

├── lib.rs

└── main.rs

Finally let's not forget a .gitignore! I thought this file was created by Cargo when creating a project, and maybe it does, but I forgot which option I need to pass it for it to do so. We want git to ignore basically only the "target" generated directory.

#.gitignore

target/

Lets do some TDD

Since we created both files, lets begin with the test one.

#[cfg(test)]

pub(crate) mod tests {

#[test]

fn useless_test_to_check_project_dir_structure() {

let result = 2 + 2;

assert_eq!(result, 4);

}

}

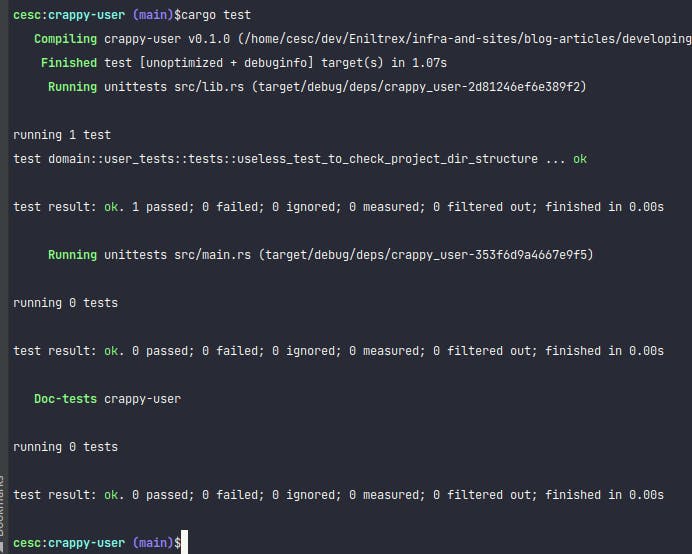

We have the platform ready! Go on the root of the project

where you have the Cargo.toml file and execute: cargo test you should see an output like this:

The first meaningful test

Lets go back to the requirements. We said we would focus on the register here. Lets write a test for that:

//src/domain/user_tests.rs

#[test]

fn register_user() {

//we are deciding here that the user is going to have only those 3 pieces of information:

let id = Uuid::new_v4();

let email = "first.user@mymail.com".to_string();

let password = "mySecretPassword".to_string();

// we would like to "create" a user by registering:

let user = User::register(id, email, password);

// then we have some claims:

assert_eq!(user.id(), id); // checking the Id is the one we expect.

assert_eq!(email, user.email_as_ref()); // checking the email is the one we expect

assert_eq!(true, user.is_registered()); // And making sure the user is registered!

}

This looks painfully OOP. Yes it is, I have no idea of FP, I am about to read a couple of books, but so far, with DDD, all the tactical patterns of DDD are basically based on OOP. There will be places where we will use more functional stuff, Rust forces them! But lets not get carried away with fDDD and keep at least some things under control (under my control, of course, using rust, which I'm a beginner of, and implementing CQRS+ES all at once is challenging enough, please don't make me do fDDD on top of it).

There are simple claims here. Mainly checking that both ID, and Email are the ones we expect plus something that tells that the user is registered, a simple flag. This last one is already a big decision, a flag is an option, the other is well, aren't all users in our system registered? Shouldn't that be "true" always? Maybe another option is to have a "user registered" struct an a "user" one so we avoid the use of flags? All of those questions are the essence of DDD. Answering them normally requires the help of the domain expert (most of the time that's the product owner in Scrum terms).

For this particular example, and for the whole project in general, I went straight forward to the most commonly used solution. Rust doesn't allow inheritance (to favor composability over inheritance). Coming from PHP where it's very common and helpful to model a domain with the help of inheritance is kind of shocking, but fair enough. And to completely disregard the flag in favor of saying that all users in the system, if they exist, that means that they are indeed registered, might be a sensible solution too, but for the sake of the example, and because it's quite common to have this flag, I went for the flag option.

The only thing left I have to say about this test is again my a disclaimer of my level of Rust. You can see that there are some getters: id(), email_as_ref() and is_registered(). I am still getting use to references and borrowing and all of that Rust paradigm. So while I know that the way I am doing it works, I am still very unsure if it's the best way or not. In general I think you want to have all the getters to return references, but you might see that I am not being consistent on that. Just a warning, that you might find what I code to not be the best usage of Rust.

If you execute now cargo check it will compile though, how is this possible? Because it ignores the test part. But if you do cargo test then you will see some expected error messages.

Uuid

I am going to use (UUIDs)[en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Universally_unique_id.. as identifiers of my aggregate. I could use other attributes just as the email address or others. But that would force me to use repository pattern to check that the email address is not really being used already. With UUIDs that won't happen. But wait, then won't I allow for different users to have repeated email addresses? Well, yes, but bear with me. I would like to explain the repository pattern later, since with ES it becomes very interesting and thick enough that it deserves a full blog post for that. UUIDs allow me now to create a User and leaving some decision for later then.

See also, in the test, that I require a UUID to create a user. UUID is not created inside the object, and when we have the full application, the UUID will need to be in the request. The client will send the UUID. Shouldn't the backend generate the UUID you might wonder. Well, it's better to make the client generate the UUID and pass it along the request. The main benefit of that procedure is that in case of faulty network, which eventually it will happen, if the request is sent twice, the backend won't create a duplicate.

All programing languages have libraries that deal with UUID so you don't need to do all the logic yourself. I am going to use a crate called "uuid":

# Cargo.toml

#...

[dependencies]

uuid = { version = "1.1.2", features = ["v4", "serde"] }

And lets add the use in our test:

// src/domain/user_test.rs

#[cfg(test)]

pub(crate) mod tests {

use uuid::Uuid;

[..]

You can execute cargo test to download the crate. This is useful if you work with an smart IDE that hints Rust problems. I am actually using PHPstorm and I'm very happy with it. The test will keep failing of course, but with one error less.

The User struct

That will be the core of our application. It's basically our only aggregate in it. Taking a look at the test, we need a struct that looks like this:

//src/domain/user.rs

use uuid::Uuid;

pub struct User {

id: Uuid,

email: String,

password: String,

is_registered: bool,

}

On our test, we used the "register" function as a named constructor, that is, a function that creates a user struct. But that won't really cut it. We need the User to be already there. On regular DDD approach, it would be desirable to force the creation of the aggregate to always be through an actual use case, like register. But on Event Sourcing you will see we will need to have a somewhat "empty" aggregate with an initial state.

Later you will understand that better, but for now, let's just add this two pieces of code on our user aggregate:

//src/domain/user.rs

impl User {

pub fn new(id: Uuid, email: String, password: String) -> Self {

User {

id,

email,

password,

is_registered: false,

}

}

pub fn id(&self) -> Uuid {

self.id

}

pub fn email_as_ref(&self) -> &str {

&self.email

}

pub fn password_as_ref(&self) -> &str {

&self.password

}

pub fn is_registered(&self) -> bool {

self.is_registered

}

}

impl Default for User {

fn default() -> Self {

User::new(Uuid::new_v4(), "init_user@gmail.com".to_string(), "defaultPassword".to_string())

}

}

We added the getters too and an implementation of Default. That will be useful for ES. Let's modify the test accordingly to our new usage of the aggregate:

//src/domain/user_test.rs

[...]

#[test]

fn register_user() {

//we are deciding here that the user is going to have only those 3 pieces of information:

let id = Uuid::new_v4();

let email = "francesc.travesa@mymail.com".to_string();

let password = "mySecretPassword".to_string();

// we would like to "create" a user by registering:

let mut user = User::default();

user = user.register(id.clone(), email.clone(), password.clone()).unwrap();

// then we have some claims:

assert_eq!(user.id(), id);

assert_eq!(email, user.email_as_ref());

assert_eq!(true, user.is_registered());

}

If you execute the test now, there's only one compilation error left that the Register function has not been found!

Event Sourcing Domain

Let's try to code the register function. I want you to ignore now the fact that in the test we are using the "register" function as named constructor. This function is not going to return a User at the end, we will modify the test later. And then, also ignore that then we need a User in place first before we can call this function upon it.

Taking into account the above, we can have a signature like this:

pub fn register(

mut self,

id: Uuid,

email: String,

password: String,

) -> Result<Self, UserDomainError> {

Note that we just added a type called "UserDomainError" as the Err branch of the Result. Let's just add this first before going deep into the event sourcing.

//src/domain/user_domain_errors.rs

#[derive(Debug)]

pub enum UserDomainError {

UserAlreadyRegistered(String),

}

Derive debug is almost necessary on all those simple enums structs. And add it to the project:

src/domain/mod.rs

mod user_domain_error;

pub use user_domain_error::*;

Yes, my common inefficient way. Don't forget the use on User:

//src/domain/user.rs

use uuid::Uuid;

use crate::domain::*;

All right let's talk about event sourcing! Without event sourcing, you might code the register function like this:

pub fn register(

mut self,

id: Uuid,

email: String,

password: String,

) -> Result<(), UserDomainError> {

if self.is_registered {

return Err(UserDomainError::UserAlreadyRegistered(self.email.value()));

}

self.id = id;

self.is_registered = true;

self.email = email

self.password = password

}

Now, that definitely passes the tests! But this is not Event Sourcing. For Event Sourcing, we need to have, first of all, domain events. Then we need to "generate" them and finally we need to apply them. This last step is what really differentiates something that it's event sourced from something that isn't.

Domain Events exists on regular DDD approach to modeling the domain. But the key difference with Event Sourcing, is that you break the aggregate functions into two parts, once that creates the domain events, and one that applies them.

Let's begin with the events.

The events

//src/domain/mod/rs

[..]

mod user_registered_event;

pub use user_registered_event::*;

//src/domain/user_registered_event.rs

use chrono::{DateTime, Utc};

use serde::{Deserialize, Serialize};

use uuid::Uuid;

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Serialize, Deserialize, PartialEq)]

pub struct UserRegisteredDomainEvent {

pub id: Uuid,

pub email: String,

pub password_hash: String,

pub occurred_at: DateTime<Utc>

}

We are adding two crates here. The chrono for UTC and the serde. Serde is probably the most used crate in Rust ecosyste. It stands for Serialize/Deserialize. Just a word of precaution here. Serialization and deserialization is very useful in general, but having objects to become all serializable eventually leads to boxes empty of meaning, which is the same as an anemic domain. I strongly discourage to use any serde #[derive(xxx)] on aggregates, you want to have control of that yourself. But for things like domain events, or any thing that looks like a DTO, it is very useful.

Add the crates to cargo.toml:

[dependencies]

chrono = { version="0.4.15", features = ["serde"] }

serde = { version = "1", features = ["derive"]}

serde_json = "1.0.82"

Generating the event

Now that we have the event, let's generate on the appropriate place, that is, the register function!

//src/domain/user.rs

impl User {

[...]

pub fn register(

mut self,

id: Uuid,

email: String,

password: String,

) -> Result<Self, UserDomainError> {

if self.is_registered {

return Err(UserDomainError::UserAlreadyRegistered(self.email));

}

let user_registered_event = UserRegisteredDomainEvent {

id,

email,

password_hash: password,

occurred_at: Utc::now(),

};

self.apply_user_registered_event(user_registered_event.clone());

Ok(self)

}

}

(Don't forget to add the uses in user.rs).

So, with ES, those "use cases" functions, such as register user, their only job is to generate the domain event and applying it.

Right now the test won't pass, well, it won't even compile, we don't have our apply function yet.

Applying the event

//src/domain/user.rs

impl User {

[...]

fn apply_user_registered_event(&mut self, user_registered_event: UserRegisteredDomainEvent) {

self.id = user_registered_event.id;

self.is_registered = true;

self.email = user_registered_event.email;

self.password = user_registered_event.password_hash;

}

}

Applying the event is what actually modifies the user!

Event Sourcing explained

With the example above, I hope you can understand the intention behind it. Basically all the functions, even the creation of the aggregate! are divided into two parts:

- generation of domain events

- Applying such domain events

For number 1, we need somehow to have an "empty" initial state. That's why the "default" trait of Rust is so useful, and it also helps with the tests. For 2 you can imagine, you need a function for applying each different domain event.

Now that's only in the domain, and I haven't explained the rest of the layers which are crucial to understand the whole concept. Because we are not going to save the aggregate in our database, instead, we are going to save in our database only the domain events.

That's why it's so important to put in a separate function how to apply each domain event. To fetch an entity, if it's event sourced, we will do the following:

- We retrieve all the events from the persistence mechanism (I mean DB)

- We start the aggregate with the initial state

- We apply all of the domain events by order.

The resulting aggregate is what Ethan Garofolo in his book calls it Projection, but for the rest of the world, a projection is the result of a read model after the aggregator has applied some or all the events.

We will see all of those concepts with practical examples in the following chapters.

Summary

Despite my lack of knowledge of Rust, I hope you could get a basic understanding of Event Sourcing, how it forces us to code the domain in a different way. We started a project like we would with a basic DDD/TDD with hexagonal architecture approach but added the Event Sourcing turn at the end.

I explained that on part 1, but let me remind you that with this project I am joining 3 different points of view: the one from Ethan Garofolo in his book. The one from Carlos Buenosvinos co-authored book and the cqrs_es Rust crate. The last one helped me greatly with my lack of knowledge of Rust, but I felt it missed some hexagonal architecture approach. Also, Rust might not be the best option to implement something that is heavily OOP oriented, but it gives some functional programming spice in it. Well, what I want to say that this project is far from perfect, but it's (going to be) a working application, and you might find it useful to get some tips and bits from here and there. I am trying to explain all the decisions I took too, so you can have a complete understanding to decide if it's going to work for you going the same path I went or not.

On the following part, we will change the User Aggregate to use value objects (didn't you feel something was fishy with the password? yes we will take care of it) and we will continue with the Event Sourcing implementation, we need to make our code more extendable, (open close principle on SOLID) so we will change many bits here and there, and a LOT of tradeoffs to discuss. I am unifying three points of view on those

If you want to check a working version, you can always see my github public repository here. That's the complete version. Still many bits to finish, but the whole concept is ready for production here. Which btw, if you stay with me, I will also explain how to do it.